A Wink and a Nod in Iran

A rare trip to the country America just bombed left me with impressions and memories as relevant today as they were when I visited the Persian country years ago.

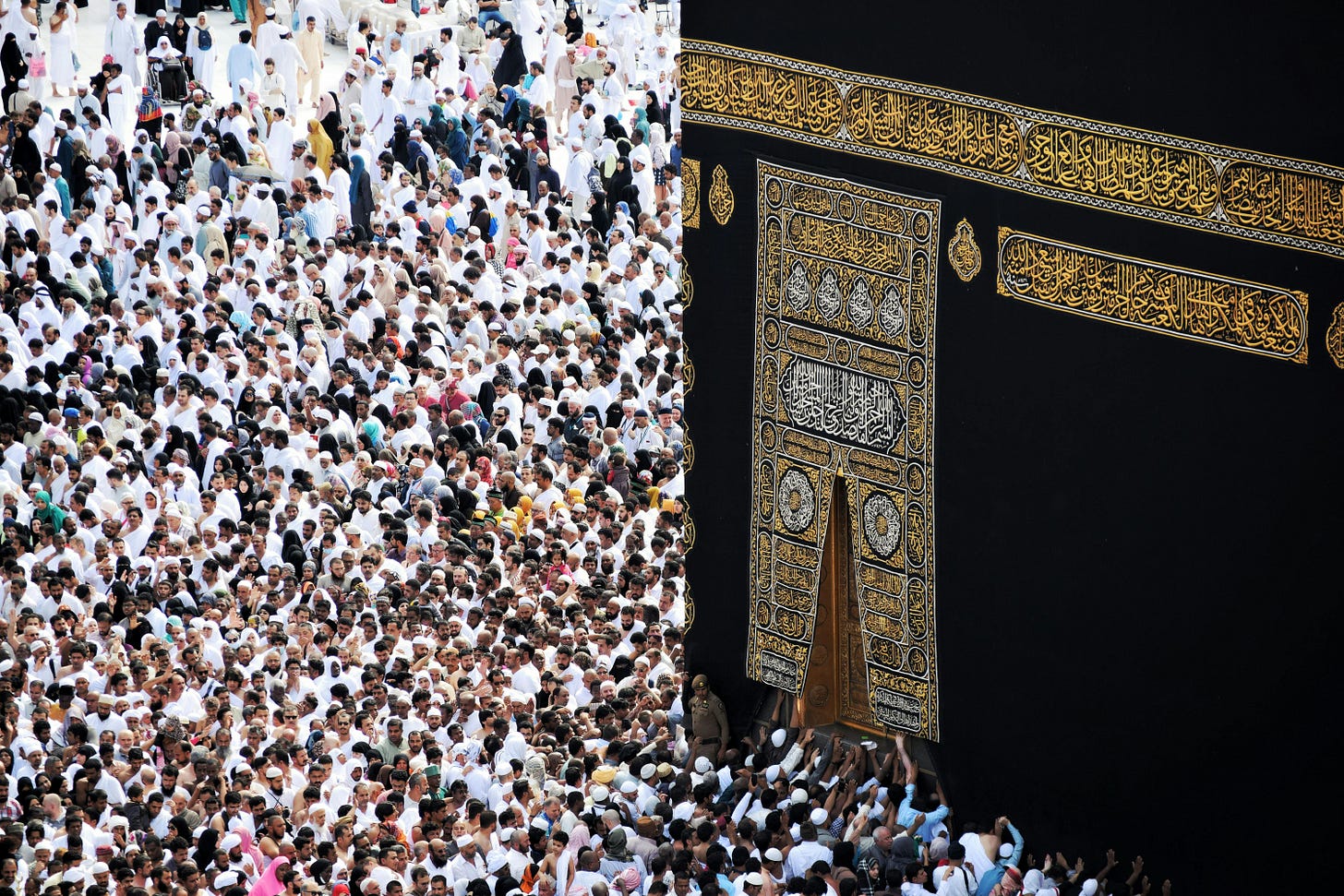

Photo by Haydan As-soendary

One brilliant morning years ago, I decided to go to Friday prayers at Tehran University while visiting Iran on a trip for the Chicago Tribune, the newspaper where I worked. I witnessed an impressive spectacle.

Thousands of Muslims crammed an outdoor plaza. They screamed and yelled as a senior cleric led prayers and delivered the theocratic regime's latest political messages. The faithful knelt on their prayer rugs, their heads bobbing up and down. In response to the imam, they repeated a chant in unison: "Death to America!"

I didn't speak or understand the local language. Still, I could tell the imam who led the service had given a loud and unquestionably hostile sermon about the United States, ending his sermon by screaming his metronomic mantra of doom into a microphone. He shook his fist in the air over his head.

Despite the hostility emanating from the faithful, I didn't feel threatened. Most of the Iranians I had met on my trip were curious why I was there. They were friendly.

But two experiences I had speak volumes about what is now underway in Iran as the country emerges from the blistering bomb and assassination attacks from Israel and its partner, American President Donald Trump.

The first episode occurred at those Friday prayers. As I watched the masses bowing and screaming their desire for American doom, one of the congregants looked at me, an unmistakably American standing on the sidelines. He glanced upward, paused mid-scream, and smiled. He then gave me a wink and a nod before he resumed bowing his head and chanting "Death to America!"

At first, the conduct of my newfound friend among the devotees amused me. Later, as I related my experience to other Iranians, I learned that many of them were like my smiling sympathizer: they went through the motions dictated by their theocratic leaders but didn't necessarily fully embrace them. Chicagoans screaming "Go Cubs" probably had more conviction about their cause than many Iranians who paid lip service to the mullahs that made "Death to America!" a Persian mantra.

One woman who served as a guide for me and my colleagues on the trip wondered why Americans became so fixated on "those old men." She explained that the mullahs didn't have that much support among the Iranian people. They ruled by force because they controlled the security forces and morality police who harshly punished violations of Shariah law, such as failure for women to wear a hijab. If they could have rejected them in a fair and free election, they probably would have. They've tried several times over the years but failed because the mullahs' rigged system cements the status quo.

As journalists, we covered the "Death to America" chants fully. It was harder to get the real story when the mullahs wouldn't let you in the country, though. Some Western news organizations have correspondents in Iran, but reporting there is restrictive and dangerous. My colleagues and I on the trip capitalized on one of those rare occasions when we could obtain a visa and actually speak with the people.

My authorized travel document spawned my second revealing experience. As we drove through Tehran's impossibly traffic-jammed streets one day, I spotted the U.S. Embassy where Iran held 52 Americans hostage for 444 days during the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979.

I decided I wanted a photo of the embassy made famous after the militant cleric, Ayatollah Khomeini, overthrew the U.S.-backed Shah of Iran. My guide warned me not to take a photo, but I foolishly ignored her and jumped out of the car. I walked to the fence surrounding the compound, snapped a few pictures, and started to leave.

The security forces instantly came at me from everywhere, on motorcycles, cars, and on foot. They are as feared and unpopular with the people as the mullahs they protect, and I soon learned why. A man dressed in a black T-shirt and jeans -- the equivalent of an undercover cop -- hopped off his motorcycle and demanded I surrender my camera. I refused. He reached for my camera, but I held onto it tightly. A tug of war ensued. He stared at me, anger in his eyes. I stared back.

My Iranian guide and friend emerged from the car to defuse the increasingly tense situation. "Give him the camera," she urged, advising me that he wanted to confiscate the film and not the camera. But I stupidly and stubbornly refused. I don't know why. The picture I took wasn't even that good. In retrospect, I resented hostile orders from a bully. I should have just given him the film, but I didn't.

Eventually, after some back-and-forth intervention from my Iranian guide, my antagonist relented. I got back in the car, and we left the scene with my unspectacular film and camera intact. He put on his motorcycle helmet and stared at me menacingly. We drove away.

What stunned me most about the encounter was the speed, ubiquity, and hostility of the security forces. It was as if they had sprung from the pavement like ghosts from the hostage crisis. I wasn't naïve enough to think that the security forces weren't following us. I suspected they had been watching us all the time. But I was surprised at the size of the force they marshaled almost instantaneously, and how quickly they surrounded me in response to something as innocent as taking a photo.

In current-day Iran, the Ayatollah and his Revolutionary Guard are alive and well despite the punishing but brief war triggered by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and President Trump.

At eighty-six and ensconced in a secret, protected location, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran's Supreme Leader, according to all reports, remains as unpopular as he was when I visited around twenty-five years ago. He communicates covertly through trusted aides. He avoids electronic communications to ease the risk that he'll be killed, either by rivals or by the Israelis who have infiltrated Iran.

I also doubt that Iran's Revolutionary Guard, its most dreaded security service, has lost any of its influence, power, and ubiquity. They reportedly surround Khamenei in his fortified location. Even though Israeli infiltrators killed many Iranian nuclear scientists, they couldn't kill the body of knowledge Iran assembled over the years studying how to enrich the uranium needed for a bomb. The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps protects such information with great zeal. Many reports suggest they had moved the enriched bomb-grade uranium beyond the reach of America's bombs.

Now the imams and their protectors are licking their wounds but have more incentive than ever to develop a nuclear weapon-- or even, God forbid, use it.

None of this means that America couldn't restore relations with Iranians who are probably tired of the hostility and economic privation caused by their theocratic leaders.

When I was in Iran all those years ago, a man approached me on the streets and asked if I was an American. When I responded affirmatively, he replied that it was good to see Americans in Tehran again. We had arrived there after the hostility generated by the 1979 hostage crisis and the overthrow of the Shah, a hated leader widely viewed as an American puppet. Yet we were treated with kindness and respect by the average Iranians we met.

President Trump's assertion that America had "obliterated" Iran's nuclear capacity is hyperbole. American pilots severely damaged the nation's ability to build a bomb, but they didn't eliminate it. There's also no doubt that the recent U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran revived anger in many of Iran's citizens. But the outrage seems like the 'rally around the flag" anger spawned by the weakening of Iran's nuclear muscle, a point of pride to many Persians. I doubt many Iranians want to drop a nuclear bomb on anyone, and I'd bet few of them would regret seeing the theocrats overthrown. The imam-led government has caused an enormous amount of personal, political, and economic pain.

President Trump mused about the U.S. engineering regime change in Iran. Few think that's possible, particularly while Iran’s arch enemy, Israel, remains a key element of American dealings with the Persian nation.

Khamenei remains holed up in his cave under the protection of the Revolutionary Guard. He continues his reign as the Supreme Leader. He reportedly has identified three potential successors to be elected by the Assembly of Experts, Iran's constitutional body responsible for choosing the next Supreme Leader.

Getting rid of him might give the world someone worse, boiling with resentment over the international humiliation the nation has just suffered. The world had a global agreement that allowed Iran to develop its nuclear power for peaceful purposes, but President Trump walked away from it, saying it wasn't good enough. He had a chance to negotiate a better deal, but he bombed the Iranians while negotiating with them for more favorable terms.

The President takes pride in his ability to cut deals. Iran presents him with a challenge for the ultimate deal – an agreement with a theocracy protected by a powerful military and security force that has little reason to negotiate with an untrustworthy American leader. The Iranian people will settle in and resume their desire to live a better life. They will no doubt have to accept another Ayatollah, but they'll probably do it with a wink and a nod.

—James O’Shea

James O’Shea is a longtime Chicago author and journalist who lives in North Carolina. He is the author of several books, the former editor of the Los Angeles Times, managing editor of the Chicago Tribune, and the former chairman of the board of the Middle East Broadcasting Networks. Follow Jim’s Substack, Five W’s + H here.